Metropolis

Germany, 1927

Director: Fritz Lang

Script: Thea von Harbou

Starring: Alfred Abel, Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlich, Rudolf Klein-Rogge

Plot

In an unspecified futuristic context, a colossal city called Metropolis rises. A strict caste system prevails. The outcasts are here a huge mass of enslaved workers, who, crestfallen, must perform from sunrise to sunset a robotic work to keep the mechanical gears of the megacity active.

The young elite, on the other hand, have fun in a different section, running track and field races. Among them is Freder, the heir; son of Joh Fredersen, lord and master of Metropolis. A harem of attractive girls is at his disposal. One of them is selected to entertain him. But while Freder and the chosen one begin to enjoy themselves, a mysterious young woman appears, surrounded by poor and ragged children. Freder forgets his life of luxury and decides to find out who is this enigmatic girl, who referring to the children said “they are your brothers”.

In the meantime, in the engine room there is an accident. Freder witnesses the catastrophe and has a horrifying vision: he sees how the jaws of Moloch open to swallow the workers, as if they were being offered to the evil creature in sacrifice. But, apparently, it was only a hallucination…

Freder decides to go see his father, who has his office in a skyscraper called “New Tower of Babel”….

Fredersen has an assistant named Josaphat. The lord and master of Metropolis is disappointed with him, because he has learned about the “accident” through his son and not through his second in command. The same happens when Grot, one of the foremen, hands him some plans that some workers were carrying in connection with the catastrophe that occurred in the engine room. As a result, Fredersen fires Josaphat. Freder, the son, tries to make his father think again, “What would happen if the workers rebelled against you? Freder catches up with Jehoshaphat, preventing him from committing suicide, and proposes that from now on he work for him. Freder wants to go to “the depths”, with “his brothers”. In the meantime, Jehoshaphat will wait for him at home.

Once in the depths of Metropolis, Freder switches roles with one of the boiler workers, who handles needles. The boss’s son instructs the worker to go to Josaphat’s house and they both wait for him there.

Fredersen, meanwhile, instructs a sinister vampire-like individual to keep an eye on his son…

The worker, disguised in Freder’s clothes, sets off for Jehoshaphat’s house. But while he is in the limousine, he is approached by the prospects of a nightclub called “Yoshiwara” (with a quote from Oscar Wilde: “He who would conquer his vices must succumb to them”). Unable to resist the temptation (women, dancing, gambling and fun) the worker tells the chauffeur that instead of going to Josaphat’s house as ordered by Freder he should go to the Yoshiwara….

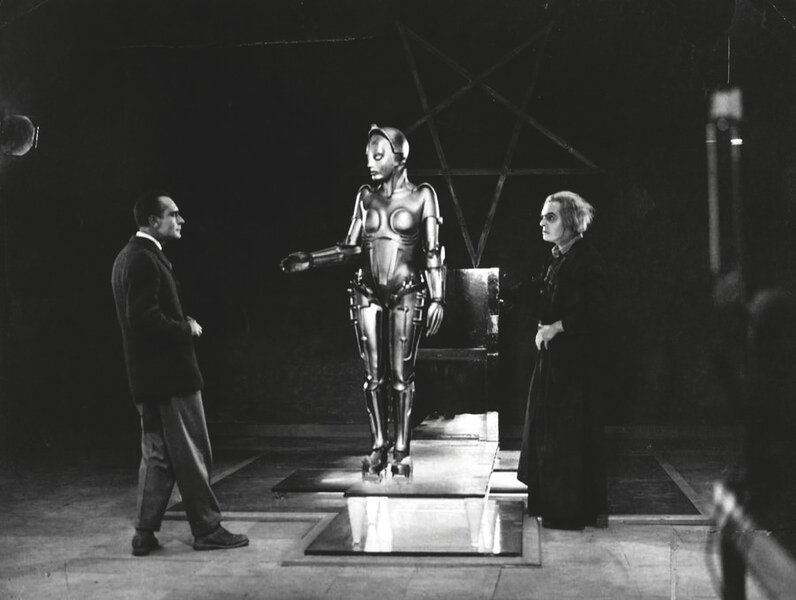

In the meantime, Rotwang shows Fredersen his creation: a bionic robot created from the remains of a certain “Hel”. The inventor, who lost his hand and wears a prosthesis is sure that the creation of artificial life compensates him for it. The master of Metropolis asks the scientist what the strange blueprints his workers carry in their pockets mean. After a thorough examination, Rotwang replies that the blueprints show the 2,000-year-old catacombs beneath Metropolis. They both decide to go there to see what the workers are interested in there.

Freder, who continues as a worker handling the hands of the clock, is warned that a meeting will take place in the catacombs and goes there as one more worker. In that subway place a cult takes place, officiated by Maria, the young woman who captivated Freder at the beginning, telling him that those poor children were his brothers. Maria tells the legend of the Tower of Babel, an analogy to the city of Metropolis. Babel was erected by thousands of slaves, who “although they spoke the same language did not understand each other”. The young priestess-prophetess explains that the project failed and the construction of the Tower collapsed because a mediator between “the head” and “the hands” was missing. That mediator is “the heart”. Mary says that, again, in Metropolis, the advent of such a mediator (i.e., the messiah) must be awaited. Freder, hearing all this, feels predestined, and when the workers withdraw he appears before Mary, saying that he is ready to assume the messianic functions.

Fredersen and Rotwang spy through a hole in the cavern walls. The owner of the city commissions his trusted scientist to build a robot in the shape of the girl…

When Fredersen leaves, Rotwang chases Maria through the catacombs until he catches her. She had arranged to meet Freder at the cathedral. He goes there, and is very disappointed not to find her. In the cathedral there are statues that refer to the seven deadly sins. There are also allusions to the Apocalypse, and to the Great Whore of Babylon, the Scarlet Woman.

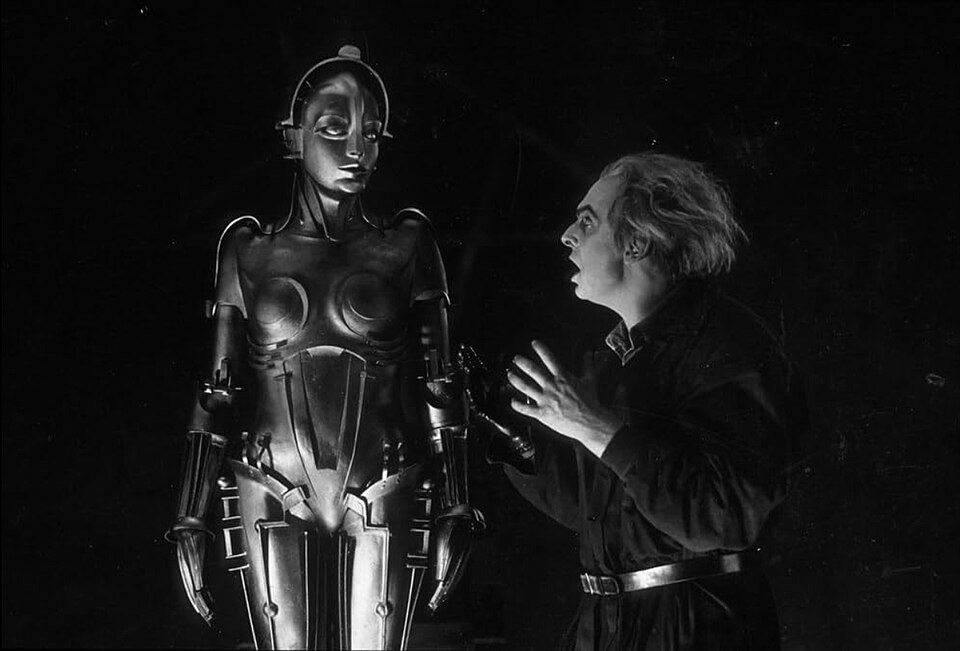

Rotwang tasks his android with destroying Fredersen, his son and his city. But for his plan to succeed, he must make the robot look like Maria.

Meanwhile, Fredersen’s sinister henchman locates the worker who, in Freder’s clothes, had been ordered to go to Josafat’s house (and instead went on a spree at the “Yoshiwara”). That worker is Georgy, with the number 11811.

Freder goes to see Josaphat, and discovers that Georgy had not gone there as planned. As soon as Freder leaves, Fredersen’s henchman appears at Jehoshaphat’s house. He tries to bribe him, but Josafat does not allow himself to be corrupted. The sinister character shows a card showing who he works for: the “Central Bank of Metropolis”.

Meanwhile, Rotwang tries to force Maria for his experiment with the robot. Freder hears her scream and runs to her aid… He walks through a maze of closing doors and can do nothing to stop the scientist from breathing Maria’s life into his bionic robot.

Fredersen orders the “new” Maria, Rotwang’s automaton, to destroy all the work of the original Maria.

From being a holy prophetess, Maria has become the Whore of Babylon, the Scarlet Woman of the Apocalypse, who performs lustful dances in the “Yoshiwara”, inflaming the passions of men and turning one against the other. At the sight of this, Freder collapses. It takes time for him to recover. But when he comes to his senses, supported by his friend Jehoshaphat, he decides to take the role of “mediator” (of Messiah) to lead the workers against tyranny and oppression. Fredersen, on the other hand, hopes that the workers will riot and thus have the perfect excuse to repress them…

There are now two Marias, the original (who is still alive) and her clone, her double, the automaton that Rotwang has endowed with her appearance. The treacherous Rotwang is plotting to displace Fredersen, to take control of Metropolis instead.

The fake Maria incites the masses of workers to revolt against the machines (being a machine herself). The mob heads for the central machine, intent on destroying it. The flock heads for the slaughterhouse: The workers are clearly about to fall into a trap.

Meanwhile, Freder and Josaphat on the one hand, and the real one on the other, try to avoid catastrophe and unmask the imposter.

Metropolis is inundated by a flood, but Freder, Josafat and Maria manage to save the children. The workers are unaware of this. When the foreman informs them that their children have disappeared, the workers despair, and blame the “witch” for what has happened. The mob seeks her out to burn her at the stake, unaware that there are two Marias (which will undoubtedly lead to confusion).

For his part, Rotwang tries to catch the original Maria, because he sees in her “Hel”, the divine and idealized woman…

Comment

Before George Orwell wrote his “1984”, the seventh art had already left for posterity a masterpiece of the dystopian genre. “Metropolis”, whose complete version appeared in Argentina a little more than a decade ago, shows a nightmarish, mechanized and robotic society; it is visionary and warns, with large doses of social criticism, about the consequences of a dehumanized hyper-industrial society.

Buñuel said that “Metropolis” has two readings, one for “laymen” and the other for “initiates”. Fredersen makes the gesture of the hand on the chest (famous for Napoleon, but also performed by Marx, and apparently a sign of recognition in the bosom of Freemasonry). The androide-golem is seated on a throne under the inverted pentagram, of clearly satanic connotations. Rotwang is the prototypical mad scientist à la Frankenstein. A hundred years ahead of his time, he already proposes the creation of artificial life (“the man-machine of the future”), which today is being seriously considered by the advocates of robotics. Black magic and transhumanism go hand in hand.

The atmosphere is excellent, especially in scenes like the one in the catacombs, when Maria is pursued by Rotwang through crypts in which skulls and skeletons can be seen.

Also worthy of note is Maria’s scene as the Scarlet Woman, with Freder’s hallucinations and apocalyptic prophecies. The film can be considered as a parable. In fact, Maria’s clone leading the masses to their own destruction is reminiscent of the strategy of social manipulation exercised from the apex of the pyramid and known as controlled dissent.

It shows how fickle and manipulable the masses can be, which will always act in one way or the opposite depending on who is leading them.

The conclusion of the film, once the evil mad scientist Rotwang has been defeated, offers a moral that is both simple and profound: Between the head and the hands, the heart must always mediate. This is true for individuals as well as for societies. And here the “head” of Metropolis, a city that archetypically represents an organic society, is Fredersen; the “hands” are the workers (their spokesman being their foreman Grot) and the “heart” is Freder, the mediator, the “messiah” announced by the prophetess Maria.

She (and her clone) is masterfully played by Brigitte Helm. As the real Maria, the actress manages to convey an aura of great goodness and purity, while in the role of the automaton created by Rotwang, her facial expressions and gesticulations testify to great wickedness and lewdness. The contrast is enormous. Worthy of mention is the scene in which the Maria-robot dances libidinously on the Yoshiwara, causing the bourgeoisie present there to lose control.

The Japanese name Yoshiwara, by the way, means “The Good Lucky Meadow”, and was the name given to the brothel district in Edo (present-day Tokyo) during the Tokugawa shogunate.

The writer Thea von Harbou, wife of the director, was in charge of the script with the collaboration of Lang himself.

“Metropolis” combines social criticism (Lang’s original intention) with metaphysics. Thea von Harbou, who was passionate about India, had a great interest in mystical themes. The film contains numerous elements of an initiatory nature. The city of Metropolis itself probably alludes to New York, the “new Babylon”, a vertical city, full of skyscrapers (modern equivalents of ziggurats and obelisks). We also see throughout the footage numerological, geometric symbolism; the importance of “time” (an element of the demiurge) is emphasized through the symbolism of clocks (not only in the machines Freder tries to control). Rotwang’s house, old and with gargoyle figures on the facade, as well as the gothic cathedral contrast powerfully with the rest of the architecture of that vertical, futuristic asphalt jungle.

The director of photography was Karl Freund, who a few years later would do the same job in the USA for Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931).

Get Metropolis HERE!

(This is an affiliate link. I may earn a commission if you purchase through these link, at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.)